DeepSeek: Innovation with Open Source Software

As I write this post, the newspaper headlines are focused on the record decline in value of tech shares, especially chip manufacturer Nvidia, following the release of the Open Source DeepSeek Large Language Model and platform.

Most of the extensive news coverage has focused on the tech business and the likelihood that it represents a bubble, especially for the Generative AI companies, OpenAi, Anthrpopic Google and the like. The other ,main focus has been geopolitical, with China having caught up with the USA in AI development.

For education, DeepSeek can be seen as good news. The domination of Generative AI by large tech companies has priced out public sector EdTech development. Here the big news is that DeepSeek is open source, freely available on the HuggingFace platform. The company is purely focused on research rather than commercial products – the DeepSeek assistant and underlying code can be downloaded for free, while DeepSeek’s models are also cheaper to operate than OpenAI’s o1.

As the Guardian newspaper reports, Dr Andrew Duncan, the director of science & innovation at the UK’s Alan Turing Institute, said the DeepSeek development was “really exciting” because it “democratised access” to advanced AI models by being an open source developer, meaning it makes its models freely available – a path also followed by Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta with its Llama model.

“Academia and the private sector will be able to play around and explore with it and use it as a launching,” he said.

Duncan added: “It demonstrates that you can do amazing things with relatively small models and resources. It shows that you can innovate without having the massive resources, say, of OpenAI.”

Its interesting to hear the motivation put forward by DeepSeek CEO, for open source. As Alberto Romero has written in his Algorithmic Bridge newsletter, in a rare interview for AnYong Waves, a Chinese media outlet, DeepSeek CEO Liang Wenfeng emphasized innovation as the cornerstone of his ambitious vision:

we believe the most important thing now is to participate in the global innovation wave. For many years, Chinese companies are used to others doing technological innovation, while we focused on application monetization—but this isn’t inevitable. In this wave, our starting point is not to take advantage of the opportunity to make a quick profit, but rather to reach the technical frontier and drive the development of the entire ecosystem.

DeepSeek has developed a completely different approach to the big tech companies who have focused on ever increasing use of hardware to scale Large language Models. And is so doing they have greatly reduced both the financial and the environmental cost of developing such technologies. This may well be a vindication of the policy of prioritising educational spending in China. Romero point out startups and universities can train top AI models and world-class human talent respectively in China. He says “DeepSeek—contrary to Google, OpenAI, and Anthropic—publishes a lot of papers on frontier research, architectures, training regimes, technical decisions, innovative approaches to AI, and even things that didn’t work.”

DeepSeek doesn’t solve all the problems associated with Generative AI. It doesn’t stop the so called hallucinations, it doesn’t solve the problems with bias and it is still only a productive language model. But through innovation DeepSeek has greatly reduced the need for vast amounts of power, has shown there are alternative approaches to demand for leakage amounts of capital investments and has provided an free and Open Source model for further research and innovation.

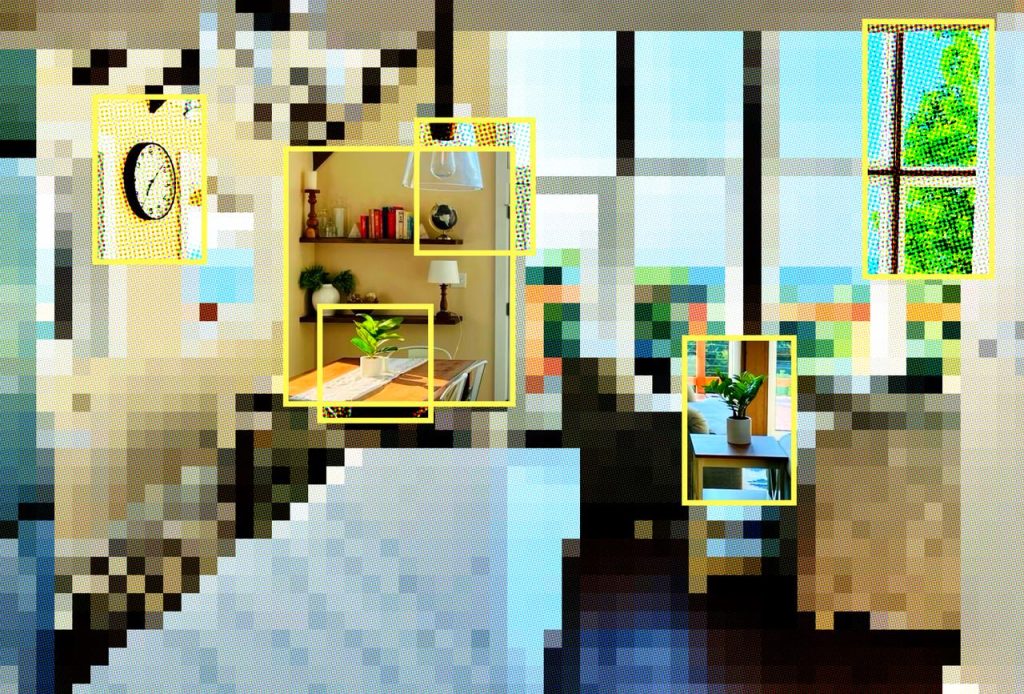

About the image

'Morning View' is part of the artist's series, 'Algorithmic Encounters': By overlaying AI-generated annotations onto everyday scenes, this series uncovers hidden layers of meaning, biases, and interpretations crafted by algorithms. It transforms the mundane into sites of dialogue, inviting reflection on how algorithms shape our understanding of the world.