AI and Ed: pitfalls but encouraging signs

In August I became hopeful that the hype around Generative AI was beginning to die down. Now I thought we might get a gap to do some serious research and thinking about the future role of AI in education. I was wrong! Come September and the outpourings on LinkedIn (though I can' really understand how such a boring social media site became the focus for these debates) grew daily. In part this may be because there has now been time for researchers to publish the results of projects actually using Gen AI, in part because the ethical issues continue to be of concern. But it may also be because of a flood of AI based applications for education are being launched almost every day. As Fengchun Miao, Chief, Unit for Technology and AI in Education at UNESCO, recently warned: "Big AI companies have been hiring chief education officers, publishing guidance for teachers, and etc. with an intention to promote hype and fictional claims on AI and to drag education and students into AI pitfalls."

He summarised five major AI pitfalls for education:

- Fictional hype on AI’s potentials in addressing real-world challenges

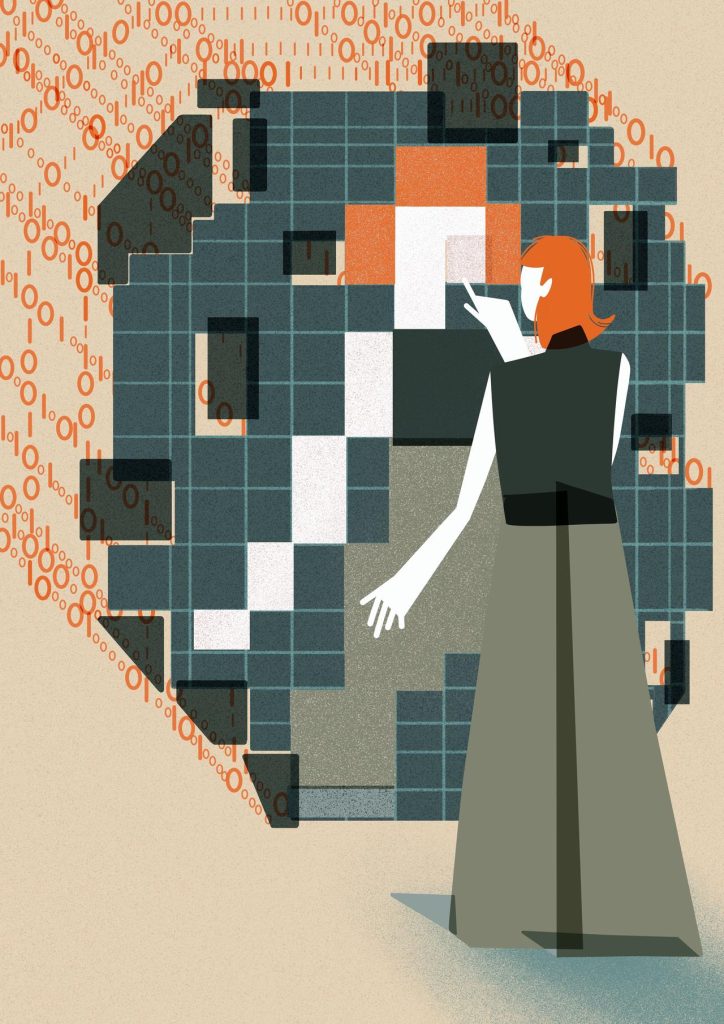

- Machine-centrism prevailing over human-centrism and machine agency undermining human agency

- Sidelining AI’s harmful impact on environment and ecosystems

- Covering up on the AI-driven wealth concentration and widened social inequality

- Downgrading AI competencies to operational skills bound to commercial AI platforms

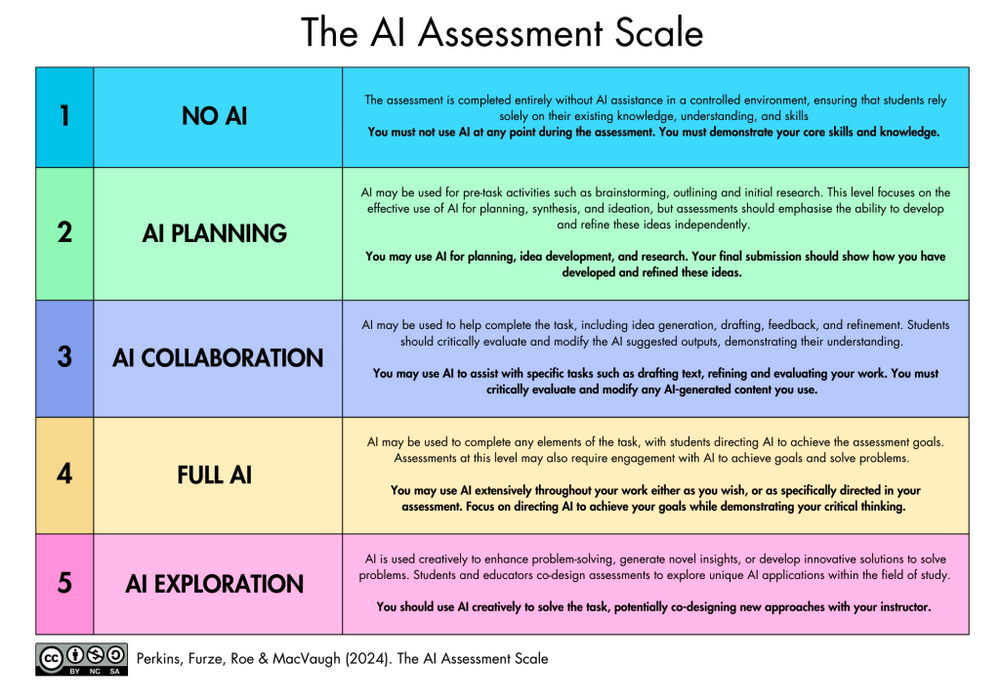

UNESCO has published five guiding principles in their AI competency framework for students:

2.1 Fostering critical thinking on the proportionality of AI for real-world challenges

2.2 Prioritizing competencies for human-centred interaction with AI

2.3 Steering the design and use of more climate-friendly AI

2.4 Promoting inclusivity in AI competency development

2.5 Facilitating transferable AI foundations for lifelong learning

And the Council of Europe are looking at how Vocational education and Training can promote democracy (more on this to come later). At the same time the discussion on AI Literacy is gaining momentum. But in reality it is hard to see how there is going to be real progress in the use of AI for learning, while it remains the preserve of the big tech companies with their totally technocratic approach to education.

For the last year, I have been saying how the education sector needs to itself be leading developments in AI applications for learning, in a multi discipline approach bringing together technicians and scientists with teachers and educational technologists. And of course we need a better understanding of pedagogic approaches to the use of AI for learning, something largely missing from the AI tech industry. A major barrier to this has been the cost of developing Large Language Models or of deploying applications based on LLMs from the big tech companies.

That having been said there are some encouraging signs. From a technical point of view, there is a move towards small (and more accessible) language models, bench-marked near to the cutting edge models. Perhaps more importantly there is a growing understanding than the models can be far more limited in their training and be trained on high quality data for a specific application. And many of these models are being released as Open Source Software, and also there are Open Source datasets being released to train new language models. And there are some signs that the education community is itself beginning to develop applications.

AI Tutor Pro is a free app developed by Contact North | Contact Nord in Canada. They say the app enables students to:

- Do so in almost any language of their choice

- Learn anything, anytime, anywhere on mobile devices or computers

- Engage in dynamic, open-ended conversations through interactive dialogue

- Check their knowledge and skills on any topic

- Select introductory, intermediate and advanced levels, allowing them to grow their knowledge and skills on any topic.

And the English Department for Education has invited tenders to develop an App for Assessment, based on data that they will supply.

I find this encouraging. If you know of any applications developed with a major input from the education community, I'd like to know. Just use teh contact form on this website.