Adoption and impact

When we talk about education and training we tend to focus on teachers and trainers in vocational schools. But there is a whole other sector known as L&D - Learning and Development. According to the Association for Talent Development, the term learning and development,

encompasses any professional development a business provides to its employees. It is considered to be a core area of human resources management, and may sometimes be referred to as training and development, learning and performance, or talent development (TD).

Phil Hardman is a researcher and L&D professional. Her weekly newsletter is in interesting because of her focus on pedagogy and AI. And in last weeks edition she looked at development with in L&D in 2024 and asked how we might progress from adoption of to impact with AI in L&D in 2025. It seems to me here analysis accurately portrays where we wre in the use of vocational education and training.

First she draws attention to her finding that in L&D teams, I- around 70% were using tools like ChatGPT, Claude, and Co-Pilot, but were not telling their management.

They were using it mostly for functional tasks:

- Writing emails

- Summarising content

- Creating module titles

- Basic creative tasks like generating activity ideas

But by late 2023, she says, aL&D users gained confidence and began using generic AI tools to tackle more specialised tasks like:

- Needs analyses

- Writing learning objectives

- Designing course outlines

- Creating instructional scripts

- Strategic planning

But Phil Hardman says in her view the shift toward using AI for more specialised L&D tasks revealed a dangerous pattern in reduced quality. “While AI tools like ChatGPT improved performance on functional tasks requiring little domain knowledge (like content summarisation and email writing), they actually decreased performance quality by 19% for more complex, domain-specific tasks that were poorly represented in AI's training data.”

This she calls "the illusion of impact where L&D professionals speed up their workflows and feel more confident about their AI-assisted work, but in practice produce lower quality outputs than they would if they didn’t use AI.”

In explaining the reasons for this she draws attention to “Permission Without Direction. While organisations granted permission to use AI tools, they provided little strategic direction on how to leverage them effectively.”

She goes on to say “L&D is a highly specialised function requiring specific domain knowledge and skills. Generic AI tools, while powerful, were not optimised for specialised L&D tasks like needs analyses, goal definition, and instructional design decision-making.”

She concludes that “The massive adoption of AI in L&D creates an unprecedented opportunity, but realising its potential requires a fundamental shift in how we think about and implement technology as an industry.”

I wonder if we are facing the same dangers in vocational education and training. It is notable that AI seems to be viewed as a good thing in supporting increased efficiency for teachers, but far less attention is being paid to whether generalised AI tools are leading to better and more effective learning. And equally although most vocational schools are allowing teachers to use AI, there still appears a lack of strategic approaches to its adoption.

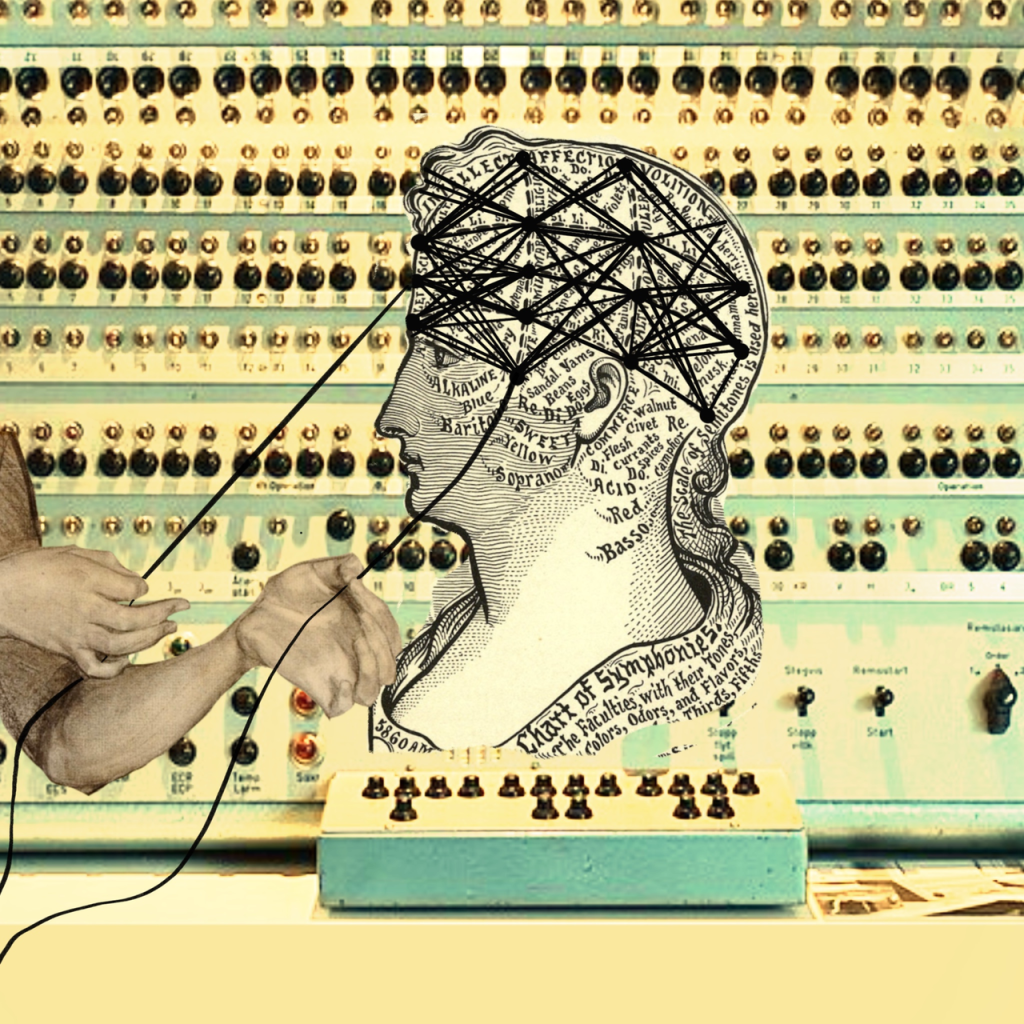

About the Image

Turning Threads of Cognition' is a digital collage highlighting the historical overlay of computing, psychology, and biology that underpin artificial intelligence. The vintage illustration of a head (an ode to Rosalind Franklin, a British chemist who discovered the double helix of DNA) is mapped with labeled sections akin to a phrenology chart. The diagram of the neutral network launches the image into the modern day as AI seeks to classify and codify sentiments and personalities based on network science. The phrenology chart highlights the subjectivity embedded in AI’s attempts to classify and predict behaviors based on assumed traits. The background of the Turing Machine and the two anonymous hands pulling on strings of the “neural network,” are an ode to the women of Newnham College at Cambridge University who made the code-breaking decryption during World War II possible. Taken together, the collage symbolizes the layers of intertwined disciplines, hidden labor, embedded subjectivity, and material underpinnings of today’s AI technologies.