AI skills and competences for teachers

UNESCO have long been active in AI in education, seeing it as a critical support for the United Nations Sustainability Goal SDG 4 for which they are the lead agent: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. There are three main strands to their work:

- AI and the Future of Learning

- Guidance for Generative AI in education and research

- AI Competency Frameworks for Students and Teachers

In a flurry of announcements and posts on LinkedIn over the summer, Fengchun Miao, Chief of the Unit for Technology and AI in Education at UNESCO, has released details of forthcoming initiatives in this field.

In 2022 UNESCO published the “K-12 AI Curricula: A mapping of government-endorsed AI curricula”, the first report on the global status of K-12 AI curricula. “All citizens need to be equipped with some level of competency with regard to AI. This includes the knowledge, understanding, skills and values to be ‘AI literate’ - this has become a basic grammar of our century,” said Stefania Giannini, Assistant Director-General for Education of UNESCO.

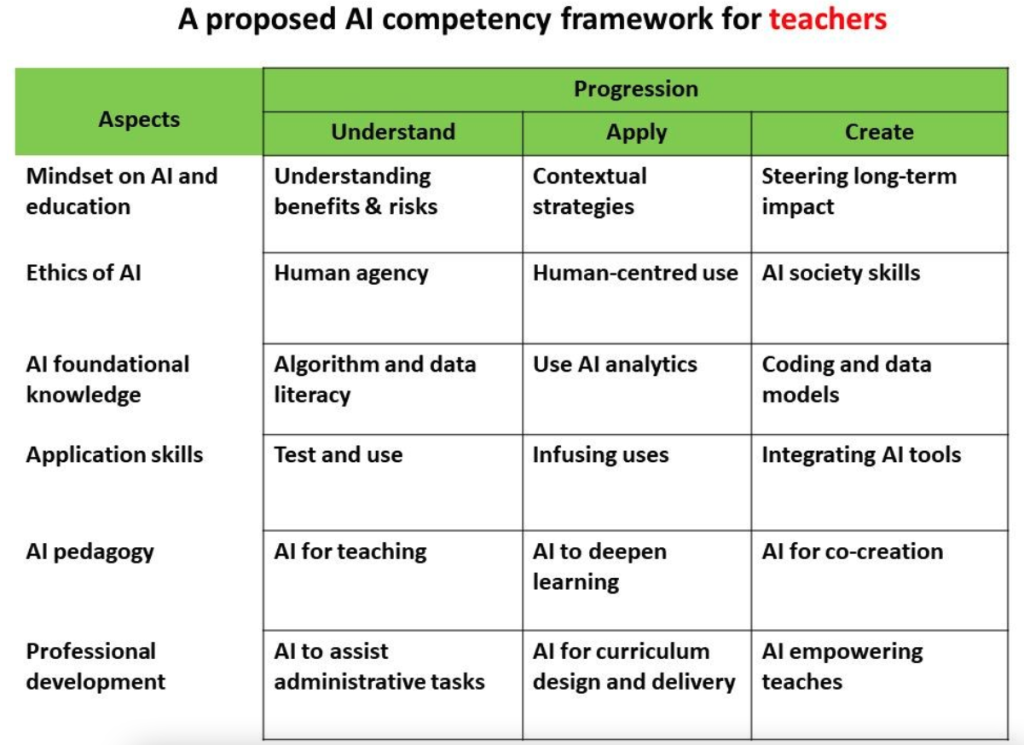

Building on this work, UNESCO have released two draft Competencey Frameworks, one on AI for students and the other AI for teachers. According to Fenchung Miao "The AI competency framework for teachers will define the knowledge, skills and attitudes that teachers should possess to understand the roles of AI in education and utilize AI in their teaching practices in an ethical and effective manner."

The drafts of the two AI competency frameworks will be presented and further refined during UNESCO's Digital Learning Week which takes place in Paris from 4-7 September 2023.

The EU funded AI pioneers project is also committed to identifying AI competences for teachers and trainers in Vocational Education and Training and Adult Education based on the EU DigCompEdu Framework, At first site, although there may be some differences in how the Frameworks are presented there appears to be no barriers to incorporation of the UNESCO Framework within DigCompEdu.

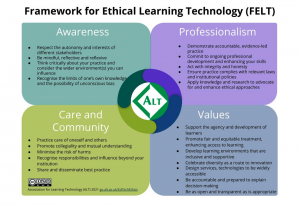

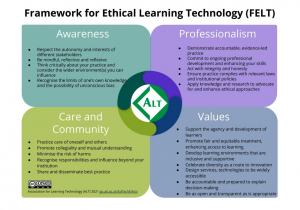

I have written before that despite the obvious ethical issues posed by Artificial Intelligence in general - and particular issues for education - I am not convinced by the various frameworks setting down rubrics for ethics, often voluntarily and often developed by professionals from within the AI industry. But I am encouraged by UK Association for Learning Technology's (ALT) Framework for Ethical Learning Technology, released at their annual conference last week. Importantly, it builds on ALT’s professional accreditation framework, CMALT, which has been expanded to include ethical considerations for professional practice and research.

I have written before that despite the obvious ethical issues posed by Artificial Intelligence in general - and particular issues for education - I am not convinced by the various frameworks setting down rubrics for ethics, often voluntarily and often developed by professionals from within the AI industry. But I am encouraged by UK Association for Learning Technology's (ALT) Framework for Ethical Learning Technology, released at their annual conference last week. Importantly, it builds on ALT’s professional accreditation framework, CMALT, which has been expanded to include ethical considerations for professional practice and research.