The danger of Lock Ins

One fear from researcher in educational technology and AI is lock in. It happened before. Companies compete in giving a good deal for applications and services but lack of interoperability leaves educational organisation stuck if they want to get out or change providers. It was big news at one time with Learning Management Systems (LMS) but slowly the movement towards standards largely overcame that issue. But with the big tech AI companies still searching for convincing real world use cases and turning their eyes on education it seems it may be happening again.

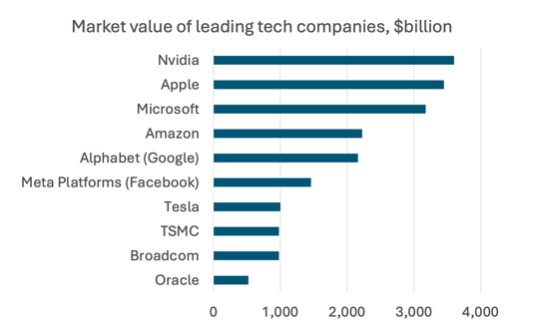

OpenAI have said it will roll out an education-specific version of its chatbot to about 500,000 students and faculty at California State University as it looks to expand its user base in the academic sector and counter competition from rivals like Alphabet. The rollout will cover 23 campuses of the largest public university system in the United States, enabling students to access personalized tutoring and study guides through the chatbot, while the faculty will be able to use it for administrative tasks.

Rival Alphabet (that’s Google to you and me) has already been expanding into the education sector, where it has announced a $120 million investment fund for AI education programs and plans to introduce its GenAI chatbot Gemini to teen students' school-issued Google accounts."

And of course there is Microsoft who have been using sweetheart deals to their Office suite and email services to education providers effectively locking them in the Microsoft world including Microsoft’s AI.

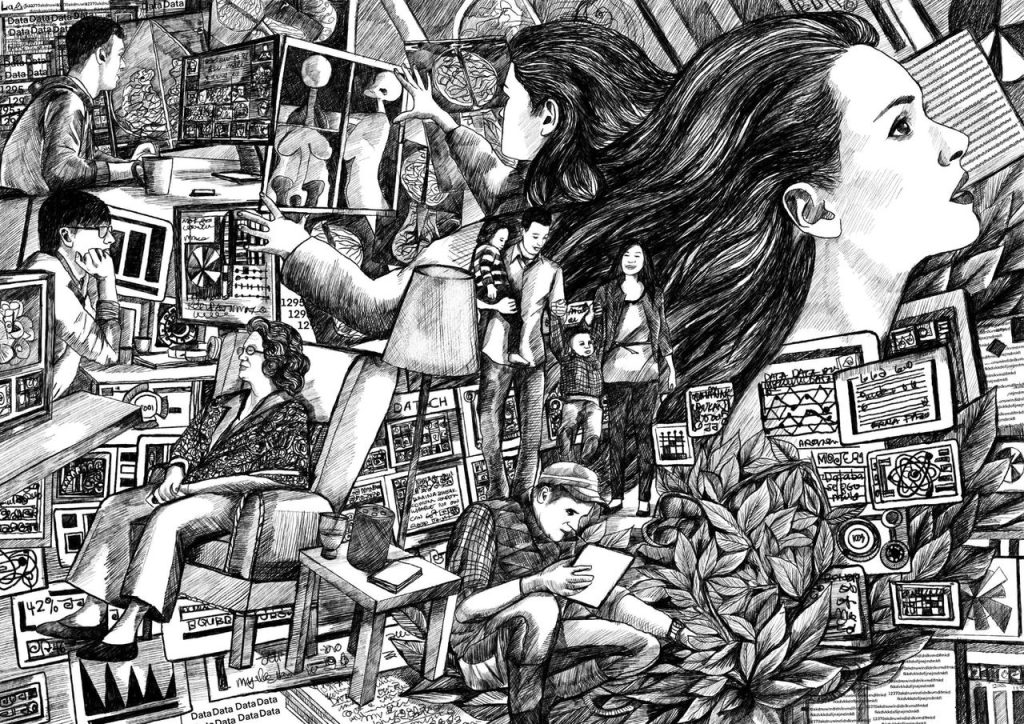

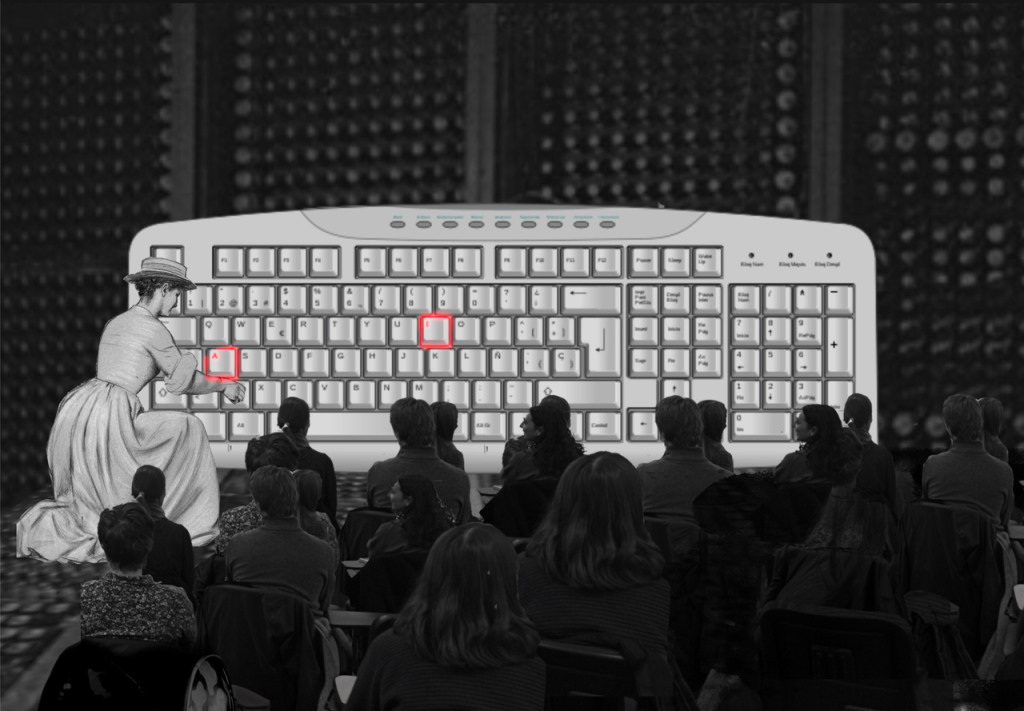

About the Image

This surrealist collage is a visual narrative on education about AI. The juxtaposition of historical and contemporary images underscores the tension between established institutions of learning and the evolving, boundary-pushing nature of AI. The oversized keyboard, with the “A” and “I” keys highlighted in red, serves as a focal point, symbolising the dominance of AI in contemporary discourse, while the vintage image of the woman in historical attire kneeling at the outdated keyboard symbolises a reclamation of voices historically marginalised in technological innovation, drawing attention to the need for diverse perspectives in educating students about future of AI. Visually reimagining the classroom dynamic critiques the historical gatekeeping of AI knowledge and calls for an educational paradigm that values and amplifies diverse contributions.