Does generative AI lead to decreased critical thinking?

As I have noted before LinkedIn has emerged as the clearing house for exchanging research and commentary of AI in education. And in this forum, the AI skeptics seem to be winning. Of course the doubts have always been there: hallucinations, bias. lack of agency, impact on creativity and so on. There are also increasing concerns over the environmental impact of Large Language Models. But the big one is the emerging research into the effectiveness of Generative AI for learning.

This week a new study from Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University found that increased reliance on GenAI in the workplace leads to decreased critical thinking.

The study surveyed 319 knowledge workers and found that higher trust in AI correlates with reduced critical analysis, evaluation, and reasoned judgment. This pattern is seen as particularly concerning because these essential cognitive abilities - once diminished through lack of regular use, are difficult to restore.

The report says:

Quantitatively, when considering both task- and user-specific factors, a user’s task-specific self-confidence and confidence in GenAI are predictive of whether critical thinking is enacted and the effort of doing so in GenAI-assisted tasks. Specifically, higher confidence in GenAI is associated with less critical thinking, while higher self-confidence is associated with more critical thinking. Qualitatively, GenAI shifts the nature of critical thinking toward information verification, response integration, and task stewardship. Our insights reveal new design challenges and opportunities for developing GenAI tools for knowledge work.

Generative AI is being sold in the workplace as boosting productivity (and thus profits) through speeding up work. But as AI tools become more capable and trusted, it is being suggested that humans may be unconsciously trading their deep cognitive capabilities for convenience and speed.

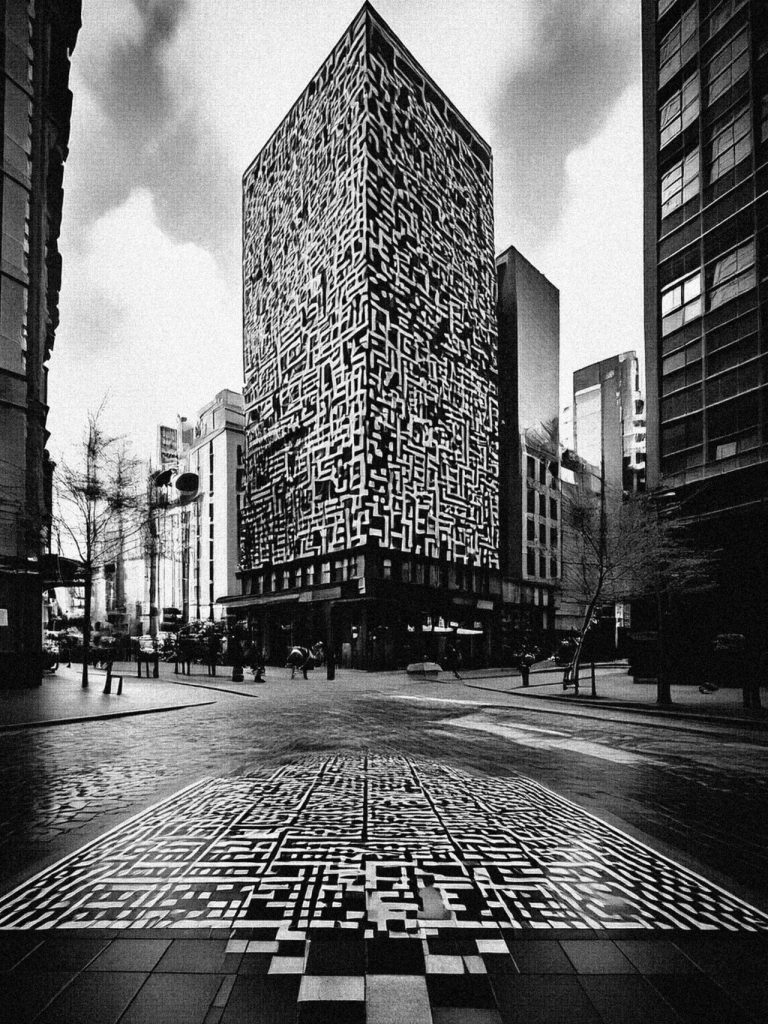

About the Image

Giant QR code-like patterns dominate the cityscapes, blending seamlessly with the architecture to suggest that algorithmic systems have become intrinsic to the very fabric of urban life. Towering buildings and the street are covered in these black-and-white codes, reflecting how even the most basic aspects of everyday life— where we walk, work, and live — are monitored. The stark black-and-white aesthetic not only underscores the binary nature of these systems but also hints at what may and may not be encoded and, therefore, lost—such as the nuanced “color” and complexity of our world. Ultimately, the piece invites viewers to consider the pervasive nature of AI-powered surveillance systems, how such technologies have come to define public spaces, and whether there is room for the “human” element. Adobe FireFly was used in the production of this image, using consented original material as input for elements of the images. Elise draws on a wide range of her own artwork from the past 20 years as references for style and composition and uses Firefly to experiment with intensity, colour/tone, lighting, camera angle, effects, and layering.