What is the purpose of Vocational Education and Training?

Is Artificial Intelligence challenging us to rethink the purpose of Vocational Education and Training? Perhaps that is going too far, but there are signs of questions being asked. For the last twenty five years or so there has been a tendency in most European countries for a narrowing of the aims of VET, driven by an agenda of employability. Workers have become responsible for their own employability under the slogan of Lifelong Learning. Learning to learn has become a core skill for students and apprentices, not to broaden their education but rather to be prepared to update their skills and knowledge to safeguard their employability.

It wasn’t always so. The American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer John Dewey believed “the purpose of education should not revolve around the acquisition of a pre-determined set of skills, but rather the realization of one's full potential and the ability to use those skills for the greater good.” The overriding theme of Dewey's work was his profound belief in democracy, be it in politics, education, or communication and journalism and he considered participation, not representation, the essence of democracy.

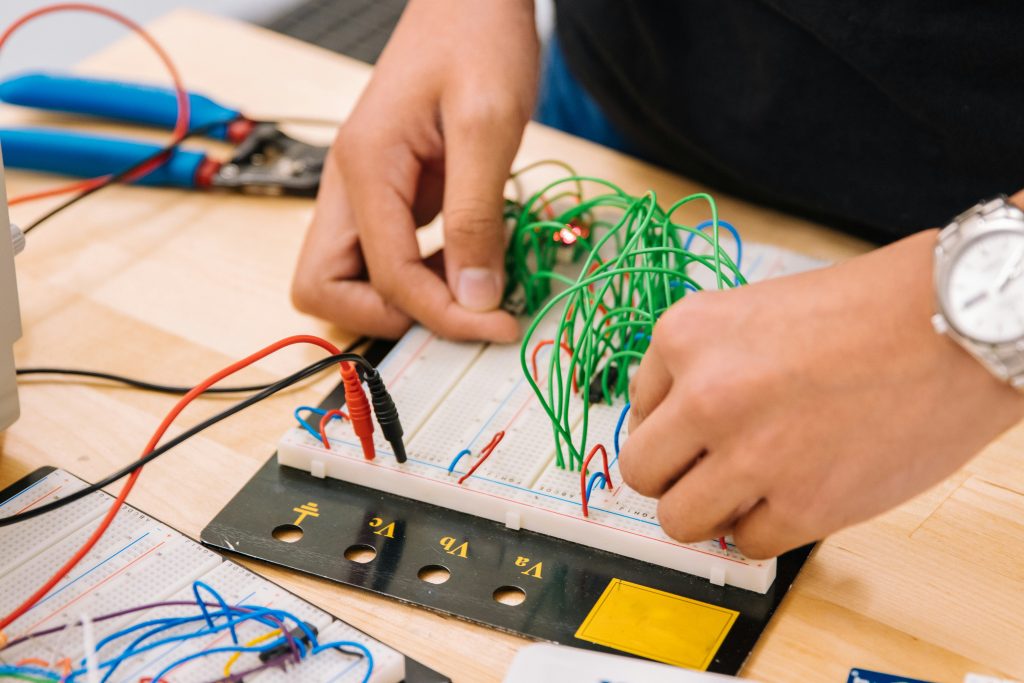

Faced with the challenge of generative AI, not only to the agency and motivation of learners, but to how knowledge is developed and shared within society, there is a growing understanding that a broader approach to curriculum and learning in Vocational Education and Training is necessary. This includes a more advanced definition of digital literacy to develop a critique of the outputs from Large Language Models. AI literacy is defined as the knowledge and skills necessary to understand, critically evaluate, and effectively use AI technologies (Long & Magerko, 2020) including understanding the capabilities and limitations of AI systems, recognising potential biases and ethical implications of AI-generated content and developing critical thinking skills to evaluate AI-produced information .

UNESCO says their citizenship education, including the competence frameworks for teachers and for students, builds on peace and human rights principles, cultivating essential skills and values for responsible global citizens. It fosters criticality, creativity, and innovation, promoting a shared sense of humanity and commitment to peace, human rights, and sustainable development. Fenchung Miao from UNESCO has said the AI competency framework for students proposed the term of "AI society citizenship" and provided interpretation in multiple sections. Section 1.3 of the Framework, AI Society Citizenship says:

Students are expected to be able to build critical views on the impact of AI on human societies and expand their human centred values to promoting the design and use of AI for inclusive and sustainable development. They should be able to solidify their civic values and the sense of social responsibility as a citizen in an AI society. Students are also expected to be able to reinforce their open minded attitude and lifelong curiosity about learning and using AI to support self actualisation in the AI era.

The Council of Europe says Vocational Education and Training is an integral part of the entire educational system and shares its broader aim of preparing learners not only for employment, but also for life as active citizens in democratic societies. Social dialogue and corporate social responsibility are seen as tools for democratising AI in work.

Renewing the democratic and civic mission of education underlines the importance of integrating Competences for Democratic Culture (CDC) in VET to promote quality citizenship education. This initiative aims to support VET systems in preparing learners not only for employment but also for active participation as citizens in culturally diverse democratic societies. By embedding CDC in learning processes in VET, the Council of Europe aims to ensure that VET learners acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to participate fully in democratic life.

The Council of Europe Reference Framework for Democratic Culture and the Unesco AI Competence Framework can provide a focus for a wider understanding of AI competences in VET and provide a challenge for how they can be implemented in practice.

Such an understanding can shape an educational landscape that leverages AI while safeguarding human agency, motivation, and ethics. As generative AI advances, continuous dialogue and investigation among all educational stakeholders are essential to ensure these technologies enhance learning outcomes and equip students for an AI-driven future.

References

Dewey, J. (1916) Democracy and Education: an introduction to the philosophy of education, New York: Macmillan. https://archive.org/stream/democracyandedu00dewegoog#page/n6/mode/2up. Retrieved 4 May 2024

Long, D., & Magerko, B. (2020). What is AI Literacy? Competencies and Design Considerations. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems

UNESCO (2024) AI Competency Framework for Students, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391105